Birds in the West

"The Bald Eagle"

with Barry M. Thornton

Out my back porch I am fortunate to watch the antics of a nesting pair

of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). It is a fascinating experience,

one that even my Brittany Spaniel has come to share by raising his head

and cocking his ears in anticipation when their sharp whistling cries

echo in the neighbourhood. He appears to know that the cry is the greeting

call of one of the eagles at the nest as it calls to it's incoming mate,

or, a warning call to other eagles that have trespassed on this pair's

aerial territory. Whichever, he seems to understand that he will soon

see the flight of one of these massive birds of prey as they come into

view with wide spread wings and outstretched bright yellow legs and

claws.

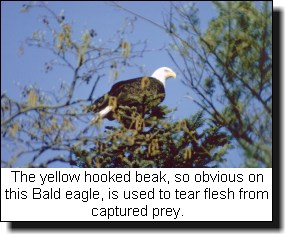

In

my travels throughout B.C. I have been fortunate to watch the Bald Eagle

in Interior skyline mountains and along Coastal streams and inlets.

They are massive birds, measuring 3 feet from head to tail, and weigh

from 7 to 10 pounds. The males have a wingspan of about 7 feet while

the females are larger, some reaching 14 pounds with a wingspan up to

8 feet. Measure that on the carpet, or, have someone six feet tall stretch

their arms fully upward to get a true picture of just how big are these

largest of North American birds of prey! In

my travels throughout B.C. I have been fortunate to watch the Bald Eagle

in Interior skyline mountains and along Coastal streams and inlets.

They are massive birds, measuring 3 feet from head to tail, and weigh

from 7 to 10 pounds. The males have a wingspan of about 7 feet while

the females are larger, some reaching 14 pounds with a wingspan up to

8 feet. Measure that on the carpet, or, have someone six feet tall stretch

their arms fully upward to get a true picture of just how big are these

largest of North American birds of prey!

It has been said that the Bald Eagle is truly an all North American

bird being the only eagle unique to this continent. It is known to inhabit

the regions of the northern reaches of Alaska and Canada, south to northern

Mexico. The Golden Eagle is the only other eagle common to North America.

Subadult Bald Eagles can be mistaken for the Golden Eagle because it

takes four years for them to attain the white head and tail of an adult

bird. It is interesting to know that another large bird, the Turkey

Vulture, is often mistaken for the Bald Eagle. However, up close, the

bright red head and neck of the Turkey Vulture make it obvious. As a

general rule I have found the use of the 'five finger view' a good check

to distinguish between an immature Bald Eagle and a Turkey Vulture in

flight.

When soaring and circling overhead, the five primary flight feathers

of the Turkey Vulture spread out like the fingers on your hand. But,

the Bald Eagle flight feathers remain together, almost cupped while

soaring. Turkey Vultures have been expanding their territory in recent

years so don't be surprised if that Bald Eagle overhead is in fact a

Turkey Vulture. flight.

When soaring and circling overhead, the five primary flight feathers

of the Turkey Vulture spread out like the fingers on your hand. But,

the Bald Eagle flight feathers remain together, almost cupped while

soaring. Turkey Vultures have been expanding their territory in recent

years so don't be surprised if that Bald Eagle overhead is in fact a

Turkey Vulture.

Bald Eagles have increased substantially since the banning of DDT in

the 70's. They are no longer rare and endangered, rather their status

has been upgraded in recent years and they are close to being taken

completely off the list of endangered species in the lower 48 states.

Bald Eagles mate for life and build huge nests in the tops of large

trees near the coast and along rivers and lakes. Nests are re-used year

after year with twigs and branches being added to the nest each year.

Some nests have been known to reach 10 feet across and weigh as much

as 1500 pounds. Bald Eagles may range over great distances, but, they

usually return to nest near where they were raised.

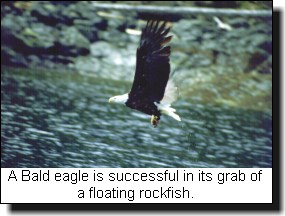

The

staple food for most Bald Eagle is fish, but they will feed on almost

anything they can catch including ducks, rodents and snakes. Because

of their obvious preference for spawning salmon they are a common sight

along all northwest coastal rivers. The

staple food for most Bald Eagle is fish, but they will feed on almost

anything they can catch including ducks, rodents and snakes. Because

of their obvious preference for spawning salmon they are a common sight

along all northwest coastal rivers.

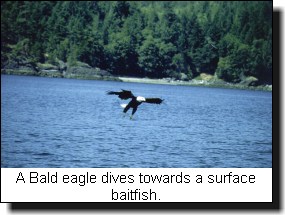

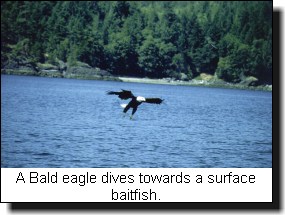

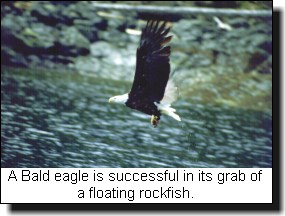

I like to think I have a pet Bald Eagle on one of the coastal islands

where I fish on a regular basis. This particular bird is almost always

seen on the high branches of a windswept Douglas fir. When I arrive

in the area I have found that it will dive down in a classic strike

should I throw some baitfish on the surface. All it takes is a sharp

whistle on my part to get a responsive cry from the eagle, then a wide

sweep of my arms to show the fish I am throwing out. The eagle will

wait a few minutes, until my boat has drifted clear of the baitfish,

and then it will launch itself from it's aerie. As it gets closer to

the floating fish it extends its bright yellow feet then glides down

over the bait grabbing the fish in one or both claws. It is interesting

to note that I have yet to see this particular eagle miss a first strike.

Bald

Eagles breed all across Canada, Alaska, and in many U.S. northern states.

In the winter these northern birds migrate south and gather in large

numbers near open water areas where fish or other prey are plentiful.

They congregate in massive numbers in small coastal estuaries where

spawned salmon are their main feed. In 1782, when the Bald Eagle was

proclaimed as the U.S. national symbol, it is estimated that there were

between 25,000 to as many as 75,000 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in

the U.S. By the early 1960s there were fewer than 450 bald eagle nesting

pairs in the lower 48 states. Now, however, it is estimated that there

are 4500 nesting pairs with at least one nesting pair in every state

in the lower 48 states. There are no Bald Eagles in Hawaii but there

are an estimated 40,000 eagles in Alaska. In Canada, no accurate numbers

appear possible, however populations are stable and increasing, and

the Bald Eagle is no longer considered threatened or vulnerable. Bald

Eagles breed all across Canada, Alaska, and in many U.S. northern states.

In the winter these northern birds migrate south and gather in large

numbers near open water areas where fish or other prey are plentiful.

They congregate in massive numbers in small coastal estuaries where

spawned salmon are their main feed. In 1782, when the Bald Eagle was

proclaimed as the U.S. national symbol, it is estimated that there were

between 25,000 to as many as 75,000 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in

the U.S. By the early 1960s there were fewer than 450 bald eagle nesting

pairs in the lower 48 states. Now, however, it is estimated that there

are 4500 nesting pairs with at least one nesting pair in every state

in the lower 48 states. There are no Bald Eagles in Hawaii but there

are an estimated 40,000 eagles in Alaska. In Canada, no accurate numbers

appear possible, however populations are stable and increasing, and

the Bald Eagle is no longer considered threatened or vulnerable.

Bald Eagles have few natural enemies but they require a large territory.

Fish contaminated with DDT and other pesticides were the deadliest killers

of eagles and other birds of prey that fed on fish where these contaminants

concentrated. Fortunately legislation in Canada and the U.S. has banned

the use of many of these poisons. It is now thought that ingested lead

shot in waterfowl, another key food of eagles, also poisoned these birds.

Legislation in the 90's banning lead shot is expected to halt this probable

poison.

Thanks to the concentrated efforts of many on both sides of the border

we can all be thankful that the Bald Eagle has become another wildlife

species success story!

"The End"

© Copyright Barry M. Thornton

Barry M. Thornton

|

In

my travels throughout B.C. I have been fortunate to watch the Bald Eagle

in Interior skyline mountains and along Coastal streams and inlets.

They are massive birds, measuring 3 feet from head to tail, and weigh

from 7 to 10 pounds. The males have a wingspan of about 7 feet while

the females are larger, some reaching 14 pounds with a wingspan up to

8 feet. Measure that on the carpet, or, have someone six feet tall stretch

their arms fully upward to get a true picture of just how big are these

largest of North American birds of prey!

In

my travels throughout B.C. I have been fortunate to watch the Bald Eagle

in Interior skyline mountains and along Coastal streams and inlets.

They are massive birds, measuring 3 feet from head to tail, and weigh

from 7 to 10 pounds. The males have a wingspan of about 7 feet while

the females are larger, some reaching 14 pounds with a wingspan up to

8 feet. Measure that on the carpet, or, have someone six feet tall stretch

their arms fully upward to get a true picture of just how big are these

largest of North American birds of prey!  flight.

When soaring and circling overhead, the five primary flight feathers

of the Turkey Vulture spread out like the fingers on your hand. But,

the Bald Eagle flight feathers remain together, almost cupped while

soaring. Turkey Vultures have been expanding their territory in recent

years so don't be surprised if that Bald Eagle overhead is in fact a

Turkey Vulture.

flight.

When soaring and circling overhead, the five primary flight feathers

of the Turkey Vulture spread out like the fingers on your hand. But,

the Bald Eagle flight feathers remain together, almost cupped while

soaring. Turkey Vultures have been expanding their territory in recent

years so don't be surprised if that Bald Eagle overhead is in fact a

Turkey Vulture.  The

staple food for most Bald Eagle is fish, but they will feed on almost

anything they can catch including ducks, rodents and snakes. Because

of their obvious preference for spawning salmon they are a common sight

along all northwest coastal rivers.

The

staple food for most Bald Eagle is fish, but they will feed on almost

anything they can catch including ducks, rodents and snakes. Because

of their obvious preference for spawning salmon they are a common sight

along all northwest coastal rivers.  Bald

Eagles breed all across Canada, Alaska, and in many U.S. northern states.

In the winter these northern birds migrate south and gather in large

numbers near open water areas where fish or other prey are plentiful.

They congregate in massive numbers in small coastal estuaries where

spawned salmon are their main feed. In 1782, when the Bald Eagle was

proclaimed as the U.S. national symbol, it is estimated that there were

between 25,000 to as many as 75,000 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in

the U.S. By the early 1960s there were fewer than 450 bald eagle nesting

pairs in the lower 48 states. Now, however, it is estimated that there

are 4500 nesting pairs with at least one nesting pair in every state

in the lower 48 states. There are no Bald Eagles in Hawaii but there

are an estimated 40,000 eagles in Alaska. In Canada, no accurate numbers

appear possible, however populations are stable and increasing, and

the Bald Eagle is no longer considered threatened or vulnerable.

Bald

Eagles breed all across Canada, Alaska, and in many U.S. northern states.

In the winter these northern birds migrate south and gather in large

numbers near open water areas where fish or other prey are plentiful.

They congregate in massive numbers in small coastal estuaries where

spawned salmon are their main feed. In 1782, when the Bald Eagle was

proclaimed as the U.S. national symbol, it is estimated that there were

between 25,000 to as many as 75,000 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in

the U.S. By the early 1960s there were fewer than 450 bald eagle nesting

pairs in the lower 48 states. Now, however, it is estimated that there

are 4500 nesting pairs with at least one nesting pair in every state

in the lower 48 states. There are no Bald Eagles in Hawaii but there

are an estimated 40,000 eagles in Alaska. In Canada, no accurate numbers

appear possible, however populations are stable and increasing, and

the Bald Eagle is no longer considered threatened or vulnerable.